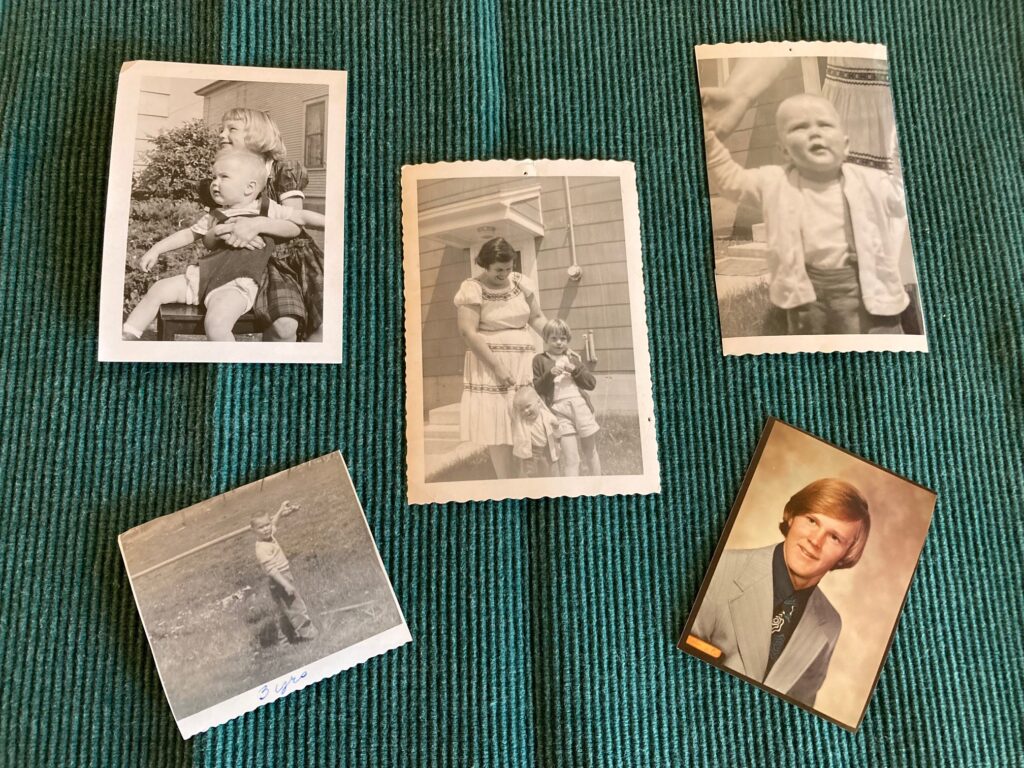

For nearly sixty-four years, my mother kept a photo of her and a newborn in her cedar chest. “Baby Charley,” as he was called, had been rushed to a nearby hospital after he was found on the backseat of a car. My nurse mother received the baby boy.

When my mom downsized and moved into a senior living community in 2018, her cedar chest didn’t make the cut. The photo did. It was nestled in a drawer in her nightstand, where it remained until we moved Mom into memory care in January 2021. Since then, that creased photo from 1954 has held a special place on my dresser.

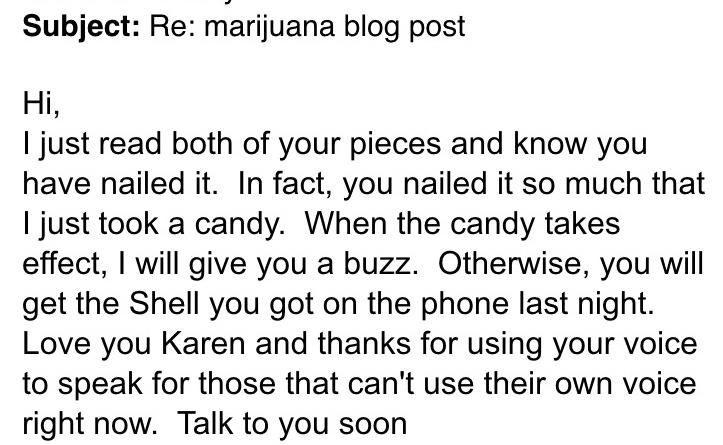

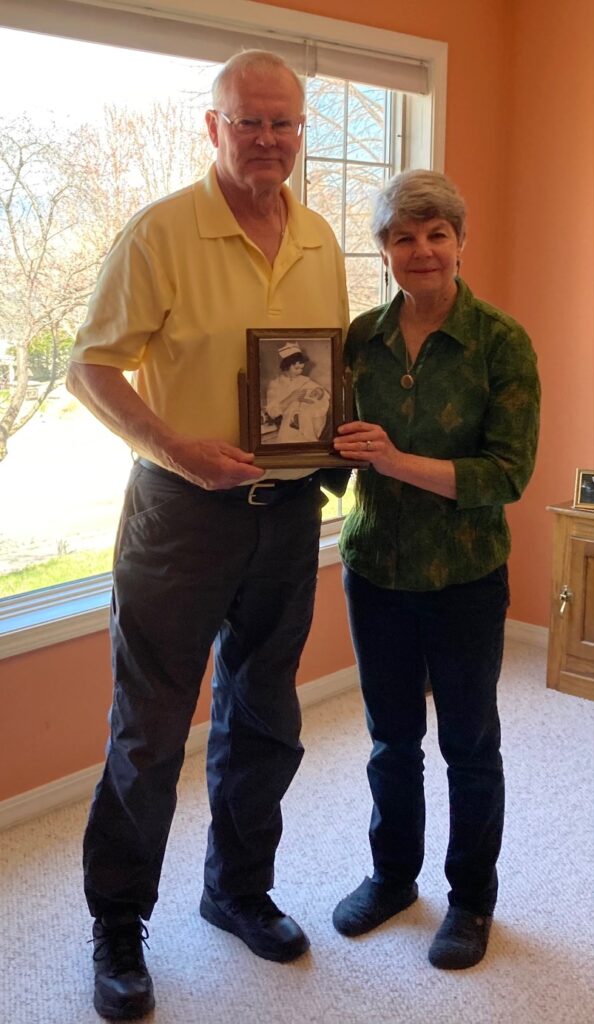

My mom died in March 2023. Last Mother’s Day, I wrote a blog post about her and Baby Charley. Two weeks ago, I had the heartwarming experience of meeting him and his wife, whom I now know as Chris and Debbie Karlberg.

Chris never tried to find information about his birth parents, but Debbie did. Her initial attempt to learn their medical history was unsuccessful. A recent search for baby boys born October 21, 1954 in Butte, Montana led her to my post and to the realization that Chris was Baby Charley.

Debbie shared her discovery with Chris and, with his blessing, tracked down my work number and called a few days later. I learned serendipity played a hand when our secretary said a woman had called for me twice that day. We keep our telephone ringers low in the Hellgate High School library and rely on voicemail when we don’t hear the phone. But instead of leaving a message, Debbie fortuitously called again while my two colleagues were out of the library.

Emotions bubbled as Debbie told me about Chris and his “Leave it to Beaver” childhood. I shared the story of the photo and my mom’s concern for Baby Charley, even as dementia began to take hold. I was grateful the circulation desk was quiet throughout our phone call. There were no interruptions nor witnesses as tears puddled in my eyes.

I learned Chris and his adopted sister grew up in Missoula and spent summers at the home their parents built on Flathead Lake. He and Debbie had been happily married for twenty-seven years. He had two bonus sons, and their family had grown to include nine grandchildren. All lived near them. Sadly, his parents and sister had passed away.

Before ending the call, Debbie and I planned for she, Chris and I to get together in the coming days.

My mother was a gracious hostess and always had “hors d’oeuvres” and something sweet at the ready for family and friends. On the cusp of Chris and Debbie’s visit, I felt Mom’s spirit as I arranged brownies and snacks on some of her serving dishes, busying myself to allay my butterflies.

When Debbie and Chris arrived, we exchanged hugs. I escorted them into the kitchen and shared anecdotes about my mom and her dishes. They nodded and smiled, saying their mom had extended similar hospitality.

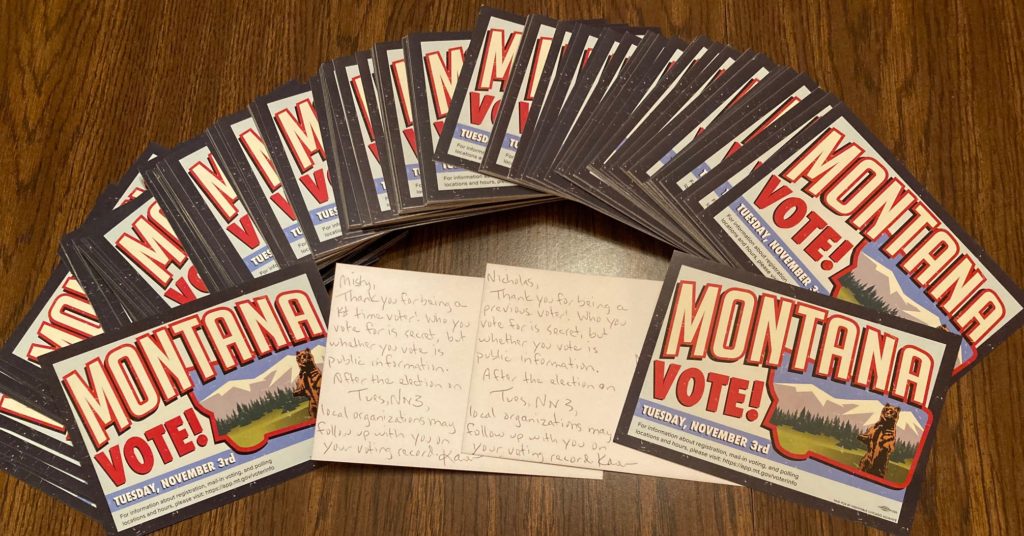

Coffee and hors d’oeuvres in hand, we settled in at the dining room table. Debbie shared some photos, though said the bulk of their albums had been packed away prior to a remodeling project.

We traded stories, and I learned that Chris’s childhood home–built by his father and grandfather in 1960 and where his parents lived until they passed away–was on West Crestline Drive. Later, his sister lived on East Crestline Drive. My family lived in Missoula from 1955 to 1964, and I returned in 1978. Chris attended first grade at Saint Anthony’s, the year before my two-year tenure there. And when I was young, my family occasionally visited our neighbor’s parents who, unbeknownst to us, lived next door to the Karlbergs. Throughout the past twenty-plus years, I’ve trekked past both Karlberg homes numerous times.

My mom and Chris’s sister shared the nickname, “Kay.” They had the same name, albeit different spelling—Catherine Ann and Kathryn Ann. Chris and Kay’s mom, Carmen, and her friend and neighbor Kay Kress were instrumental in the development of a neighborhood park. Had the opportunity arose, Debbie, Chris and I agreed our moms would have been fast friends.

Chris said he was proud of his name. His grandfather John Karlberg had had a successful contracting business and crafted many beautiful homes in Missoula. His father, Karl, had been a well-respected attorney, and his dad’s legacy lives on in Boone Karlberg. Chris displayed an entrepreneurial spirit from a young age, buying his first Napa Auto Parts store when he was only twenty-one years old.

According to Debbie, meeting Chris was the best thing that had ever happened to her. They have had a full and varied life. Both had stents as EMTs in small Montana towns. In addition, Debbie was an Emergency Services dispatcher, and Chris was a volunteer firefighter and Search and Rescue volunteer who was particularly skilled in underwater rescues.

Currently, Chris and Debbie own six Napa stores. They share a deep love and keep busy with work, caregiving for Debbie’s mom, attending grandchildren’s events and more. The day we met, they had traveled from Polson to Missoula to watch a grandson play in a tennis tournament. I later learned he won his matches.

Chris knew he was born in Butte and adopted as an infant, and he feels love and gratitude for the woman who gave him the gift of life. If she is still alive and would like to connect, he would welcome a reunion. More importantly, he understands that she may want to hold her story in the quiet of her heart.

We took pictures, and I gifted Chris one of the plush throws that had warmed my mom and me when we watched “Jeopardy” and “Wheel of Fortune.” He and Debbie nodded and smiled again when I mentioned our nightly routine. They too are fans of both shows.

I also gave them three photos and a copy of my novel Perimenopausal Women with Power Tools, that includes threads of a birth mother, a birth father, a baby, the night sky and more.

During a phone conversation this evening, Chris shared that his first-grade teacher in 1961-1962 was Sister Mary Martin Joseph. My older brother, who was in Mom’s womb when she cradled Baby Charley, was also in Sister Mary Martin Joseph’s class that year. Over speaker phone, Debbie, Chris and I shared palpable joy as we envisioned an undetectable bond between a classroom mom and a young, redheaded boy. Small world, indeed.

Across the veil that separates this life and the next, I imagine my mother’s sparkling blue eyes and jubilant smile. I believe, after nearly seventy years, she now knows that a special baby has had a wonderful life.

I’m saving my mom’s maroon throw. Perhaps I’ll have the opportunity to gift it to Baby Charley’s birth mother one day. Regardless, wherever she is, I wish her peace.